Introduction: Why Opus 4.6 Feels Different For Builders

Table of Contents

- Introduction: Why Opus 4.6 Feels Different For Builders

- Core capability upgrades vs 4.5: what actually changed

- 1M token context and compaction: how to use long context safely

- Adaptive reasoning, effort levels, and latency management

- Cost control, reliability, and beta feature risks

- Practical tips for architects and developers

- Conclusion and next steps

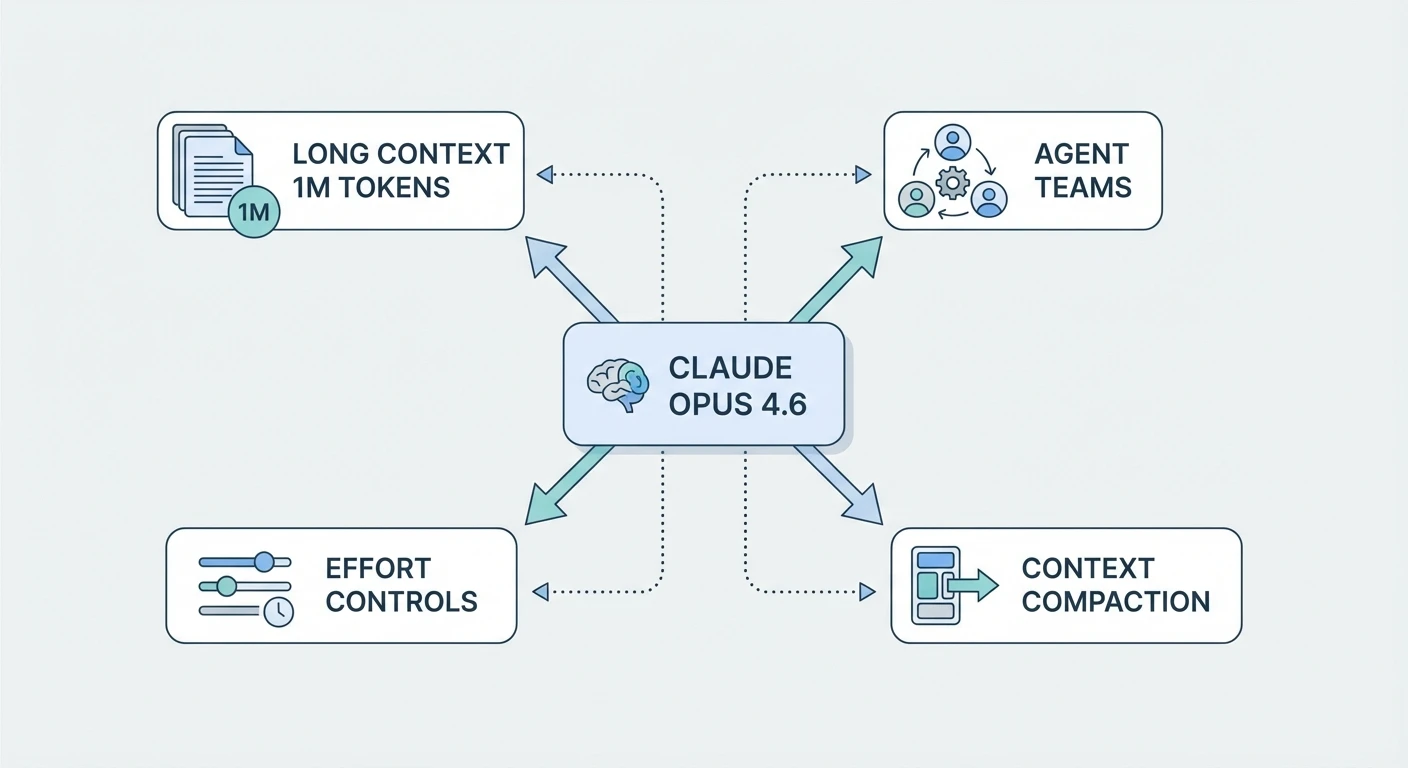

Claude Opus 4.6 is not just a slightly faster version of 4.5; paired with a secure Australian AI assistant designed for everyday and professional workflows, it changes how you design workflows, reason over code, and control cost. The model introduces a 1M token context window, agent teams, adaptive effort controls, and context compaction. The real question is simple: how do you wire this into real systems without losing reliability or blowing up spend?

You will see where Opus 4.6 is technically different from 4.5, how to configure long context and compaction, how to shape agent team behaviour, and how to tune effort parameters for latency and cost. We will also call out the rough edges that come with beta features so you can design with guardrails instead of hope, especially if you are leaning on specialist implementation services rather than building every integration from scratch.

Core capability upgrades vs 4.5: what actually changed

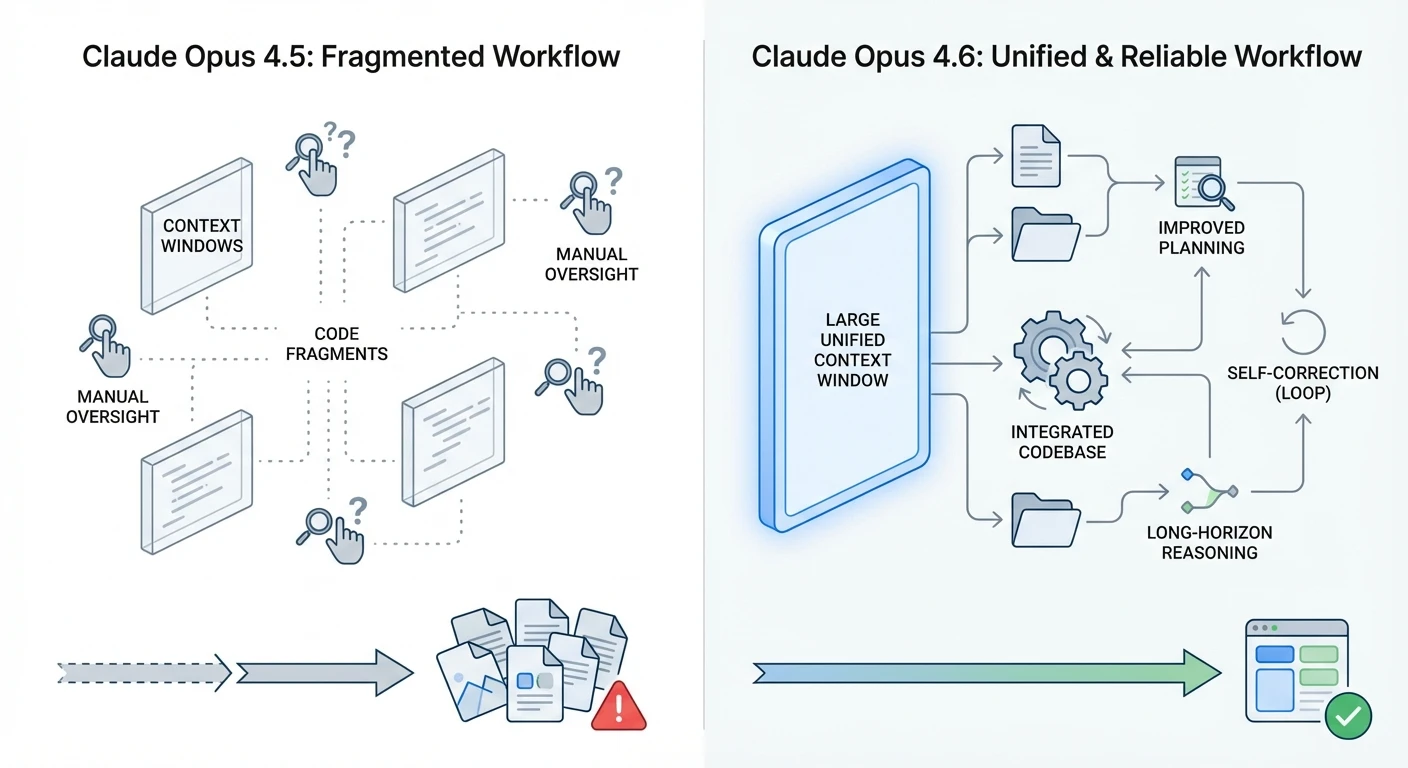

The jump from Claude Opus 4.5 to 4.6 is most obvious in coding and long-horizon tasks, and has been documented by Anthropic’s own release notes and independent industry coverage. Earlier generations could help with refactors, but only if you hand-fed tightly scoped chunks and watched them like a hawk. Context limits and weaker self-debugging meant the model would often miss cross-file effects or silently introduce regressions. With 4.6, planning and self-correction have been strengthened so the model can operate more reliably inside larger codebases, especially when combined with the extended context window.

Agentic coding is another area where the mechanics have changed. However, some experts argue that while 4.6 is clearly a step up, “more reliable” shouldn’t be mistaken for “fire-and-forget.” Even with better planning and self-correction, large, messy codebases still expose edge cases the model can misinterpret, especially when legacy patterns, partial documentation, or unconventional architectures are involved. An extended context window helps it see more of the system at once, but it can also tempt teams to shove entire repos into a single prompt instead of enforcing clear interfaces and smaller, testable changes. In practice, 4.6 looks most reliable when it’s paired with disciplined engineering workflows—version control hygiene, unit and integration tests, and human review—rather than treated as a fully autonomous refactoring engine. Opus 4.6 reaches state-of-the-art results on Terminal-Bench 2.0, a benchmark that measures a model’s ability to act through a terminal to complete realistic development tasks rather than toy exercises. That matters because the same underlying behaviour drives how well the model can navigate scripts, run tests, and iterate on fixes in a semi-autonomous loop, whether you expose a full terminal or a constrained tool layer.

In 4.5, long multi-step workflows – a research project, a non-trivial product analysis – tended to drift after many turns. The model would forget earlier constraints or contradict its own prior decisions. In 4.6, long-horizon control benefits from both the larger context window and new context compaction, which are designed to preserve salient state over many steps instead of just dropping older content. Combined with stronger self-review, the system can carry a coherent plan much further before intervention is needed.

These upgrades do not make 4.6 infallible, but they change the trade-off surface. Where 4.5 was best treated as a powerful assistant for bounded operations, 4.6 can be treated as an active participant in multi-step flows, provided you wrap it with monitoring and clear tool boundaries. The practical patterns for doing that sit on top of long context, agent teams, compaction, and effort controls; if you prefer a managed route, professional AI integration services can help map these capabilities cleanly into your existing stack.

https://www.anthropic.com/news/claude-3-5

1M token context and compaction: how to use long context safely

A context window is the span of text, code, and conversation the model can see at once. With Claude Opus 4.6’s 1M token context window (currently in beta), that span can reach roughly 750k English words, depending on formatting. Technically, this allows you to load an entire service, a book-length policy set, or a deep research bundle into a single prompt without heavy manual summarisation. Outputs with Claude Opus 4.6 can reach up to 128k tokens, similar to other cutting-edge models like Claude 3.7 Sonnet, enabling extremely long-form responses of roughly 100,000 words., which is more than enough for multi-section reports or large patches, especially when orchestrated through a bespoke automation layer rather than ad-hoc scripts.

For developers, this means you can map architectures directly: load a monolith, ask for an overview of module boundaries, then request concrete refactor plans that reference specific files and functions. The model can identify dead code, duplications, and inconsistent patterns across services because those patterns sit within its visible span. For analysts or operations engineers, you can ingest long audit logs or multi-year reports and ask targeted questions without pre-chunking into small samples.

The flip side is cost and latency. Tokens beyond roughly the 200k mark are priced at a premium, and very large prompts simply take longer to process. That is where context compaction enters. Context compaction automatically summarises and compresses older conversation segments so that you keep the important state without blindly carrying every raw token. In long-running workflows, especially agentic ones with many intermediate tool calls and partial results, this compaction reduces the risk of hitting hard limits while also helping the model focus on what is still relevant.

Treat the 1M window and compaction as dials, not defaults. Use full-scale context for operations that truly need global visibility, such as first-pass architecture mapping or end-to-end compliance review, then fall back to tighter views for routine tasks. Allow compaction to manage conversational history, but maintain your own structured memory (for example, a state object in your application) for critical facts so you have deterministic control over what is re-injected at each step; teams relying on multi-model routing strategies will find those abstractions particularly helpful.

https://www.anthropic.com/news/1m-context-opus

Adaptive reasoning, effort levels, and latency management

In Opus 4.5, extended thinking was exposed as a simple on/off switch. Opus 4.6 replaces that binary approach with explicit effort levels and adaptive reasoning, giving you more direct control over how much “brainpower” the model applies to each request—a shift called out in broader market analyses of the Opus 4.6 upgrade.

The effort parameter can be set to low, medium, high, or max, with high as the default. In practice, this affects the depth and breadth of internal reasoning steps the model is allowed to take before it returns a response. At low effort, you get quicker but more straightforward answers, suitable for simple transformations or lookups. At higher levels, the model is allowed to explore more candidate paths, cross-check intermediate steps, and perform more robust self-review, which is beneficial for intricate coding tasks or complex analytical work.

Adaptive thinking means the model is not rigidly locked to one level in all scenarios. Even when set to high, it will only escalate to more intensive reasoning when the task appears to demand it. This is particularly helpful in mixed workloads, where a single integration may handle both trivial and very complex calls. You no longer have to maintain separate configuration profiles for “fast path” and “deep reasoning” if you do not want to, although many teams still choose to expose different presets through their own APIs.

For latency management, combine effort levels with other controls. Route short, stateless operations—format conversions, basic content drafting—to medium effort with smaller context windows, and restrict max effort to endpoints that gate important decisions, such as architecture proposals or safety reviews. Instrument your workflows to log effort settings alongside response times and error rates. Over time, you will see where high effort produces visible quality gains and where it only adds cost, letting you tighten defaults without guesswork; decision frameworks like those in model selection and routing guides are useful references here.

https://www.anthropic.com/news/claude-3-5-sonnet

Cost control, reliability, and beta feature risks

Long context, agent teams, compaction, and adaptive effort are powerful, but they also shift how you think about cost and reliability. The 1M token context window lets you avoid manual chunking but can lead to large prompt sizes if you simply dump entire repositories or knowledge bases into every call. Since context usage beyond roughly 200k tokens is billed at a premium, unbounded usage can surprise finance teams if you do not set limits or quotas at the application layer.

A practical cost pattern is tiered context. Define classes of operations in your system: local (under 32k tokens), extended (32k to 200k), and full-scale (beyond 200k, using the 1M window). Only a small fraction of workflows usually need that top tier, such as first-time audits or deep investigations. Everything else can operate on smaller, more targeted slices of context that you assemble from structured data rather than raw dumps. Combine this with selective use of higher effort levels and you can keep your effective cost per successful task within predictable bounds—an approach that aligns well with how model-performance trade-off analyses recommend segmenting workloads.

On the reliability side, longer context windows reduce “context rot” – the gradual loss of coherence in long sessions – but do not fully remove it. That is why context compaction is offered as a beta capability: it helps sustain long-running workflows by summarising older segments, yet its summarisation choices may sometimes omit details you care about. Do not rely on compaction alone for critical state; maintain your own structured memory or persistent store of key decisions and constraints, and re-inject them explicitly at important checkpoints.

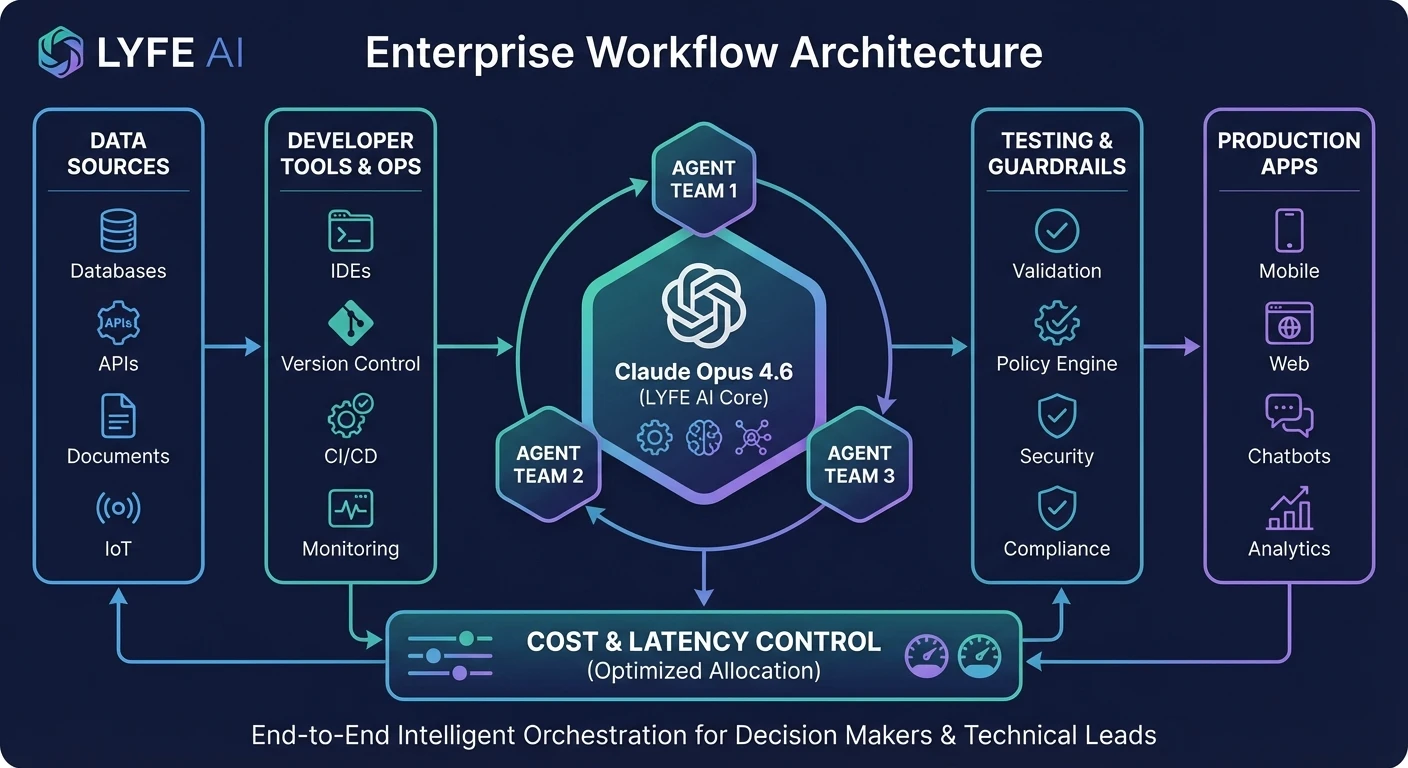

Agent teams share a similar profile. They unlock parallel work but add new failure modes such as conflicting edits, inconsistent assumptions between agents, or deadlocks in coordination. In an Australian context, where many organisations operate under strict regulatory expectations for system stability, you will want clear fallbacks if an agent stalls or produces unexpected output. That might mean timeouts with automatic rollback, or human review steps before deployment pipelines proceed; clarifying these responsibilities in your internal terms and operating conditions avoids ambiguity later.

Several of these capabilities – large context in beta, compaction in beta, and early-stage agent teams – are still evolving. Plan for change. Encapsulate them behind your own abstractions so you can tweak behaviour or even disable specific features without rewriting every consumer service. Treat the current versions as powerful tools that require engineering discipline rather than magic switches you can flip and forget; this is exactly the pattern you’ll see if you study how large organisations are adopting Opus 4.6 amid broader AI industry shifts.

https://www.anthropic.com/news/1m-context-opus

Practical tips for architects and developers

Turning the mechanics of Claude Opus 4.6 into something robust enough for production comes down to a few core habits. First, design your APIs and internal services around explicit configuration. Do not hard-code context sizes or effort levels; expose them as parameters with sane defaults so you can experiment safely. A common pattern is to ship an internal “AI config” service that centralises these knobs, making it easy to roll out changes across multiple applications—or to delegate that responsibility to a partner like Lyfe AI, which specialises in secure, configurable deployments.

Second, normalise observability. Log prompt sizes, context tiers, effort settings, error categories, and latencies. Over a few weeks you will build a picture of where Opus 4.6’s advanced features truly add value. You might discover that only 5 percent of workflows need agent teams, and that the rest run perfectly well on single-agent flows with modest context. Those insights let you trim unnecessary complexity and cost.

Third, pilot beta features on non-critical paths first. Use them in developer tooling, internal QA assistants, or sandboxed research tools before wiring them into customer-facing products. Encourage your engineers to try “breaking” long-running sessions, unusual context mixes, or awkward coordination patterns so you expose edge cases in a controlled environment. Think of this as adversarial testing for your integration, not for the model alone; tracking these pilots in a dedicated internal knowledge and experiment index helps future teams understand what has already been tried.

Finally, document your design decisions. When you decide to cap context at a certain size, or to use high effort only for specific operations, write down the rationale and the metrics that guided it. In fast-moving teams, especially across cities like Sydney, Melbourne, and Brisbane, that shared context prevents future developers from undoing carefully tuned settings just because they seem “overly cautious”. Opus 4.6 gives you fine-grained controls; lasting value comes from using them deliberately and transparently, often in combination with ongoing professional support arrangements.

https://www.anthropic.com/news/claude-3-opus

Conclusion and next steps

Claude Opus 4.6 changes what is technically possible: million-token context, stronger coding and self-debugging, agent teams, adaptive effort controls, and context compaction. But the difference between an impressive demo and a dependable system lies in how you configure those pieces. Architects and developers who treat these as engineering primitives – with clear limits, observability, and fallbacks – will unlock deep workflow shifts rather than sporadic wins, especially when they sit alongside carefully tuned automation layers and considered model-selection policies.

As you move forward, start small but design for scale: introduce long context and effort tuning where they solve concrete problems, then experiment with agent teams and beta compaction behind strong abstractions. In the final part of this series, we will step out of the engine room and look at how these capabilities reshape complete coding, finance, and knowledge workflows end to end. For now, your next move is clear: sketch your integration boundaries, list the controls you need, and begin wiring Opus 4.6 into one real workflow that matters to your team—or partner with an implementation team that already lives and breathes these patterns.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is Claude Opus 4.6 and how is it different from Claude 4.5 for developers?

Claude Opus 4.6 is Anthropic’s latest flagship model with a 1M token context window, improved planning, and better self-correction, especially for code and long-horizon tasks. Compared to 4.5, it can reason over much larger codebases, handle multi-file changes more reliably, and support features like agent teams and adaptive effort controls for cost/latency tuning.

How can I use Claude Opus 4.6 to work with large codebases in practice?

With Opus 4.6 you can load entire subsystems or repositories into the 1M token context and have the model reason across multiple files at once, instead of micro-chunking everything. In practice, teams use it for cross-file refactors, dependency analysis, architecture reviews, and long debugging sessions by streaming in relevant code and logs and letting the model plan and execute changes step by step.

What are agent teams in Claude Opus 4.6 and when should I use them?

Agent teams let you orchestrate multiple specialized AI “roles” (for example, planner, coder, reviewer) within a single workflow. You should use them when your process naturally splits into stages—such as requirements analysis, solution design, implementation, and QA—so each agent can focus on its own responsibility while sharing context inside the long window.

How do effort controls in Claude Opus 4.6 affect cost and latency?

Effort controls let you dial how hard the model thinks before answering, trading off speed and cost against depth and robustness of reasoning. Lower effort settings are useful for quick drafts, simple queries, or interactive UX, while higher effort is better for critical code changes, complex analysis, or governance workflows where mistakes are expensive.

What is context compaction in Claude Opus 4.6 and why does it matter?

Context compaction is the process of summarising or compressing long histories and large document sets so they still fit meaningfully into the 1M token window. Done well, it keeps key decisions, constraints, and references available to the model while dropping noise, which reduces token spend and improves reliability over long-running workflows and multi-step agents.

How do I stop a 1M token Claude Opus 4.6 workflow from blowing out my API spend?

You control cost by aggressively filtering inputs, compacting older context, and using different effort levels depending on the step. Many teams pair cheap pre-filters or retrieval systems with Opus 4.6, only passing in the truly relevant files, documents, or conversation slices and reserving high-effort calls for critical reasoning or code changes.

What are the main risks or rough edges when using Claude Opus 4.6’s beta features?

Beta features like agent teams and advanced effort controls can introduce unpredictable latencies, edge-case failures, or occasional over-eagerness to change code. To manage this, you should add guardrails such as strict tool permissions, automated tests on every suggested change, human-in-the-loop reviews for production workflows, and clear timeouts or fallbacks.

How does LYFE AI help Australian businesses implement Claude Opus 4.6 safely?

LYFE AI designs and builds secure Claude Opus 4.6 workflows tailored to local privacy and data residency requirements, using Australian-hosted infrastructure where needed. They handle architecture, prompt and agent design, context-compaction strategies, and cost/latency tuning so teams can get production-ready systems without having to build every integration and guardrail from scratch.

Can LYFE AI integrate Claude Opus 4.6 into my existing tools and workflows?

Yes, LYFE AI specialises in integrating Claude Opus 4.6 with existing stacks such as internal portals, CRMs, ticketing systems, and developer tooling. They can expose Opus-powered agents via chat interfaces, internal APIs, or automation platforms so your staff can use long-context reasoning and coding assistance inside the tools they already work in.

Is Claude Opus 4.6 suitable for regulated or sensitive Australian data, and how does LYFE AI handle that?

Claude Opus 4.6 can be used with sensitive data if it is deployed with the right security controls, logging, and data-handling policies. LYFE AI focuses on secure Australian deployments, including strict access controls, minimising what data is sent to the model, and designing workflows that respect compliance needs in sectors like finance, healthcare, and government.