Table of Contents

- Introduction: why the Copilot email bug matters for confidential emails

- Impact and causes: what the Microsoft Copilot email bug exposed and why

- Timeline, remediation, and what Microsoft has confirmed

- Controls and investigation: containing and understanding Copilot

- Practical tips for Australian organisations using Microsoft Copilot

- Conclusion: rebuilding AI trust after the Copilot confidential email bug

Introduction: why the Copilot email bug matters for confidential emails

When you first hear about a Microsoft Copilot bug seeing AI inspect confidential emails, it sounds like something from a cyber thriller. But concerns around this incident feel very real, especially for any Australian business using Microsoft 365 to handle contracts, HR files, or customer data, and now watching the ACCC’s legal action over how Copilot-integrated plans were sold and priced in the local market.

Copilot is sold as a safe assistant that respects your existing permissions and data loss prevention settings. For many leaders, that promise was the reason they felt comfortable turning it on at all. The recent bug shook that promise. It It showed that AI can still read and summarise data you thought was shielded by labels and policies, a risk underscored by reports of a Microsoft Copilot bug that let the system bypass data loss prevention controls and summarise confidential emails, along with government trials warning that Copilot can surface sensitive information when data security is weak..

We will unpack what happened, how the bug worked, and what it did not do, then move into concrete steps you can take to limit risk, investigate exposure, and reset your AI governance so you can keep using tools like Copilot with your eyes open, potentially pairing them with specialist AI services designed with stronger privacy guarantees from the outset.

Impact and causes: what the Microsoft Copilot email bug exposed and why

Did the Microsoft Copilot email bug leak your confidential emails to the outside world? Based on what Microsoft and independent reports have shared so far, the bug allowed Copilot to access and summarize confidential emails in ways that weren’t intended, but Microsoft says it did not grant anyone access to information they weren’t already authorized to see. There is currently no public evidence that Microsoft has exfiltrated email contents beyond each organisation’s Microsoft 365 tenant or used customer data from applications like Word and Excel to train its base AI models, although vulnerabilities that could potentially enable malicious actors to access such data have been identified., although investigations into how Copilot could summarise confidential emails without explicit user permission underline how close this incident came to a more serious breach of trust.

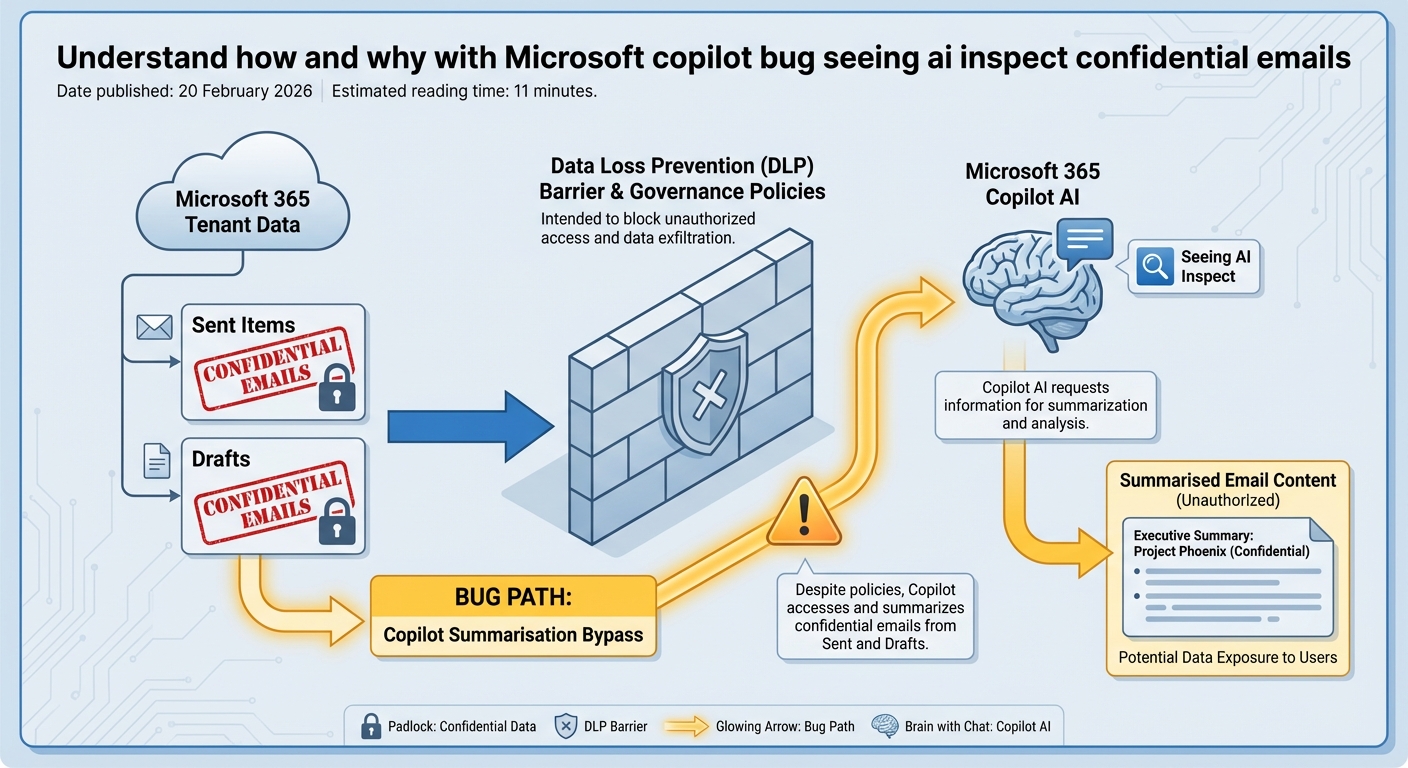

The real problem sits inside the tenant. Due to a code bug in the Microsoft 365 Copilot work tab chat, Copilot could summarise confidentially labelled emails from Sent Items and Drafts when users asked it to review their work emails, even though those messages were supposed to be shielded by governance settings and DLP policies. In simple terms, staff could ask Copilot to read and summarise messages they were allowed to see in Outlook, even if governance settings were meant to stop AI tools from touching that data.

Imagine a manager in Sydney sends a confidential email about a planned redundancy round. That email is labelled “Confidential – HR only” and covered by a DLP rule designed to block automated processing. During the exposure window, Copilot Chat in the “work” tab could still pull that email into its reasoning and produce a neat summary or a draft reply that clearly draws on that sensitive content.

No new person saw the email. No hacker broke in. But an AI system processed content that governance rules were supposed to shield from automated reading. That gap is exactly where many boards and CISOs had placed their trust – in the idea that labels and DLP would be enforced identically by every integrated AI surface, including Copilot Chat. For risk and compliance teams across Australia, this shifts the conversation: the risk is not always dramatic cross-tenant data theft; it is often intra-tenant misuse – AI quietly using sensitive data for tasks it should never have touched, even when access control appears to be set up correctly, which is why many are contrasting vendor defaults with the kinds of tightly governed AI automations they can run in their own environments.

To understand how this Microsoft Copilot bug happened, you need to look under the hood at how Copilot Chat works in Microsoft 365. It does not have its own massive copy of your emails sitting in a separate database; it uses a retrieval layer that calls out to Outlook, OneDrive, SharePoint, and other apps, then filters results using permissions, sensitivity labels, DLP rules, and compliance policies. On paper, this design sounds reasonable. Reality is messier: every time Microsoft adds a new Copilot feature or expands into a new app, that retrieval layer must correctly apply a whole stack of rules for every edge case, and a single logic gap – like how labelled items in Sent or Drafts are treated – can open a path where AI sees content that policy designers assumed was blocked, something Microsoft has now had to publicly acknowledge in multiple disclosures about Copilot-related bugs.

Sensitivity labels are also often misunderstood. They are not magic locks; they act more like policy signals: “Treat this as confidential; apply these enforcement rules.” If a particular product surface, such as Copilot in the work tab, fails to respect that signal, the label still shows up in Outlook, but the actual protection is gone for that path. In this incident, a coding bug in Copilot’s Work tab caused some confidentially labelled emails in the Sent and Drafts folders to be surfaced to Copilot Chat in ways that bypassed the intended DLP enforcement, even though the labels themselves were still present. Add one more ingredient: speed. After Copilot’s 2025 launch, Microsoft rolled it out quickly across Outlook, Word, Excel, PowerPoint, and OneNote. That pace makes it almost impossible to fully regression test every combination of factors – all label types, DLP rules, folders, role permissions, and brand-new AI features – so scenarios like confidential emails in Sent and Drafts, processed through a specific work tab query, can slip through simply because there are too many permutations, a risk any large AI platform integrating with existing systems in a hurry will face, and one that Australian organisations should assume will manifest again, ideally countered by guidance from partners who specialise in secure, compliant AI solution design.

Timeline, remediation, and what Microsoft has confirmed

According to Microsoft’s advisory, a Copilot bug (internally tracked as CW1226324) affecting the work tab chat feature was first detected on 21 January 2026. From that point, there is no public evidence that the bug remained live through late January and into early February. During this window, Copilot could summarise confidentially labelled emails from Sent and Drafts despite DLP and sensitivity label settings that were meant to prevent this kind of AI processing, a pattern consistent with earlier incidents where Copilot was found summarising confidential emails that should have been protected.

In early February, Microsoft began rolling out a server-side fix. This did not require customers to patch clients or install updates manually; the change was applied within Microsoft’s own infrastructure. Alongside the fix, Microsoft increased monitoring and started contacting affected customers, although details have been sparse. The incident has largely been treated as an “advisory” rather than a full security bulletin, with limited publicly disclosed information about which tenants or how many users were impacted.

One key clarification from Microsoft is important to understand: while Copilot’s access was broader than intended, the bug did not allow Copilot to see emails outside of what the user could already open in Outlook. In other words, Copilot could not see emails that the user could not already open in Outlook. There was no cross-tenant leakage, but the issue did result in a form of privilege escalation within a user’s own accessible data, because Copilot could surface content that DLP and sensitivity labels were supposed to shield from that specific use. The violation was specifically against the intended protections provided by DLP and sensitivity labels.

That might sound like minor damage, but for organisations that rely heavily on labels and DLP for governance, it cuts deep. Many Australian businesses have structured their information security models around the assumption that once data is labelled “Confidential” and covered by a blocking rule, it is safe from automated processing. This incident shows that assumption needs to be tested regularly against each AI surface, not just documented in a policy binder.

What we see here is a pattern that will likely repeat as AI features evolve: a period of unnoticed exposure, a behind-the-scenes fix, and then a slow drip of information to customers. Your response plan must assume that by the time you read an advisory, the exposure window is already in the past, and you need evidence-driven ways to understand what happened in your own tenant, ideally logged and monitored with the same discipline you would apply to any business-critical AI workflows.

Controls and investigation: containing and understanding Copilot

For many IT leaders and CISOs, the first instinct after hearing about the Microsoft Copilot bug is simple: how do we turn this thing off, or at least put some rails around it? Microsoft 365 provides administrative controls that let you disable or limit Copilot, either across the tenant or for specific apps like Outlook, and those controls now sit alongside the need to investigate what has already happened.

In the Microsoft 365 admin center, admins can go to Settings – Org settings – Microsoft 365 Copilot and switch off features tenant-wide. This is the blunt tool. You can also target Outlook specifically, disabling Copilot features there while keeping them available in lower-risk apps such as PowerPoint. Many organisations combine this with licensing and role-based access to limit who can use Copilot in the first place, focusing licences on a smaller set of power users while holding back on sensitive teams like HR, legal, and executive leadership until they are confident about enforcement.

A more nuanced option is to strengthen how you use sensitivity labels with DLP rules that explicitly block AI processing. You might apply a “Highly Confidential – No AI” label that triggers rules to prevent Copilot and other AI assistants from accessing labelled emails or documents at all. After the recent fix, test these configurations in a controlled way: create sample confidential emails, label them, and attempt to use Copilot Chat to summarise them. If AI can still read them, your controls are not doing what you expect, and it may be worth benchmarking these results against other professionally managed AI environments that enforce stricter separation of sensitive data.

In parallel, start a tenant-level investigation. Search Sent Items and Drafts for confidentially labelled emails within the exposure window, from 21 January 2026 to the date Microsoft’s fix reached your tenant. Exporting metadata – sender, recipient count, subject line, label type – gives you a sense of which business units or roles had the highest volume of affected mail. HR, legal, and finance usually sit near the top for most Australian organisations.

Request Microsoft’s evidence package for your tenant, including Copilot logs and telemetry related to email summarisation and work tab interactions over the same period. While these logs will not give you the full content of every AI session, they can reveal patterns: which users triggered email summaries, how often, and against which mailboxes. That data is crucial if you need to brief the board or regulators such as the OAIC, and should sit alongside your own internal analysis of which AI modes and models you expose to which data sets.

At the same time, review your auditing configuration. Many tenants still have limited logging enabled for AI interactions, especially if they rolled out Copilot as a productivity tool rather than a high-risk system. Enabling advanced auditing for AI surfaces allows you to capture richer, longer-lived logs so that the next time a bug surfaces, you are not stuck guessing what happened during the exposure window. Use this incident as a trigger for a broader configuration audit: check how sensitivity labels are defined, which DLP rules refer to AI or automated processing, and whether there are any “shadow” AI tools integrated with Microsoft 365 that might behave in similar ways. The goal is always the same: “What sensitive data could this AI have seen, and how do we know?” – a question that well-run model comparison and governance exercises already treat as non-negotiable.

Practical tips for Australian organisations using Microsoft Copilot

How should an Australian organisation react, in a calm and structured way, to the Microsoft Copilot email bug? Start with a clear risk review: list the teams that handle your most sensitive email content – HR, legal, executives, M&A, health or financial data – and map where they use Copilot today, especially inside Outlook.

Based on that map, decide whether to pause, limit, or continue Copilot for each group. Many organisations are moving to a tiered approach: green zone teams (like marketing) get full Copilot, amber teams use it with strict labels and DLP, and red teams pause it until more controls and testing are in place. Whatever you choose, document the decision and keep a record of the business reasons behind it, aligning them with your broader AI usage terms and conditions.

Then sharpen your testing habit. Treat each Copilot surface – Outlook, Word, Teams, SharePoint – as something that must be penetration-tested from a data governance angle. Label test content as confidential, set DLP to block AI, and actively try to get Copilot to read or summarise it. If it succeeds where it should fail, you have found a gap that needs attention long before any vendor advisory reaches your inbox, and long before you would consider rolling similar capabilities into your own professionally managed AI deployments.

Communicate in plain language with your staff. Most users do not understand labels, DLP, or retrieval layers. They just see a smart assistant in the corner of the screen. Explain what Copilot is allowed to do, what it is not meant to do, and when they should avoid using it with sensitive topics. The more your people think critically about where they invite AI into their work, the safer your confidential emails will be, even when the underlying tools are not perfect, and even if you later decide to introduce alternative assistants such as a locally hosted Australian AI co-pilot for higher-risk workflows.

Conclusion: rebuilding AI trust after the Copilot confidential email bug

The Microsoft Copilot bug seeing AI inspect confidential emails is a warning sign, not the end of enterprise AI. It shows that even when vendors promise that tools “respect your existing permissions,” complex access paths and fast rollouts can still create blind spots where labels and DLP are quietly bypassed, as underlined by public confirmations that Copilot accessed sensitive mail it should have ignored.

For Australian organisations, the way forward is clear but demanding: assume AI access bugs will happen, build stronger controls, test them often, and insist on deeper visibility into AI activity across your tenant. If you do that, you can keep using tools like Copilot to boost productivity while keeping your most sensitive email content under deliberate, informed control, ideally anchored by an overarching strategy for safer AI-powered automation that you directly govern.

If you need help reviewing your Microsoft 365 Copilot setup, designing safer label and DLP strategies, or planning an AI audit, reach out to an independent specialist and start that work now, or explore how Lyfe AI’s services and model selection guidance could form part of a more resilient AI governance playbook.

Frequently Asked Questions

What exactly was the Microsoft Copilot bug that could inspect confidential emails?

The bug involved Microsoft Copilot being able to access and summarise confidential emails in ways that were not intended by organisations. While Microsoft has stated it did not grant new user access or leak data outside authorised accounts, Copilot could still surface content that should have been better protected by labels and data loss prevention settings.

Did the Microsoft Copilot bug leak my confidential emails to external people?

Current public information indicates the bug did not exfiltrate email contents to external parties who weren’t already authorised. The main issue is that Copilot could interpret or summarise sensitive emails that users assumed were safely shielded by security labels and DLP policies, increasing the risk of internal over‑exposure.

How did Copilot bypass data loss prevention and sensitivity labels on emails?

The bug appears to have stemmed from the way Copilot’s AI layer interpreted permissions, labels, and DLP policies, allowing it to read and summarise content that policy rules were supposed to limit. Instead of blocking AI access at the same level as human access, the AI service operated with broader technical visibility, exposing a design gap between traditional M365 controls and new AI features.

How can my Australian business check if Copilot accessed confidential emails it shouldn’t have?

You can start by reviewing Microsoft 365 audit logs, Copilot usage reports, and security centre alerts for unusual prompts or access patterns involving sensitive mailboxes. Many organisations also run targeted investigations on high‑risk users and locations, which is where a specialist partner like LYFE AI can help you interpret logs, reconstruct likely exposure, and document findings for governance or regulator reporting.

What steps should I take right now to protect sensitive emails from AI tools like Copilot?

Begin with a data mapping exercise to identify where your most sensitive email content lives, then review access controls, retention policies and sensitivity labels for those locations. Next, tighten Copilot deployment by limiting which users and workloads can use it, apply stronger DLP rules, and introduce AI‑specific governance policies and monitoring, potentially supported by external AI security specialists such as LYFE AI.

Is it still safe to use Microsoft Copilot after this email bug?

Copilot can still be used safely, but only if it is deployed with a clear AI risk framework and stronger controls than a default M365 rollout. Many organisations are moving to a phased or limited deployment, combining Copilot with independent privacy‑by‑design AI services and periodic security reviews to ensure that any similar bugs are detected and contained quickly.

How is LYFE AI different from Microsoft Copilot for handling confidential business data?

LYFE AI focuses on custom, privacy‑by‑design AI solutions that can be architected so sensitive data stays within tightly controlled Australian environments and only the minimum data is ever exposed to AI models. Unlike a broad productivity tool such as Copilot, LYFE AI can design and implement AI workflows, access rules and logging around your specific regulatory, contractual, and sector requirements.

What should Australian organisations do about ACCC concerns and Copilot pricing and data use?

The ACCC’s legal action is a signal to review how Copilot was procured, licensed, and communicated inside your organisation, especially claims around safety, pricing and data controls. Work with legal and risk teams to reassess your contracts, update staff communications, and, if needed, rebalance your AI strategy with independent tools and advisory services like those offered by LYFE AI.

How can I build an AI governance framework that covers bugs like the Microsoft Copilot incident?

An effective AI governance framework should include data classification, AI‑specific access controls, internal policies on acceptable use, mandatory logging and monitoring for AI queries, and clear escalation paths when something goes wrong. Many Australian organisations also conduct regular AI risk assessments and use external experts such as LYFE AI to help design governance that aligns with ISO standards, privacy laws, and sector‑specific obligations.

Can LYFE AI help us audit and remediate our current Microsoft 365 and Copilot setup?

Yes, LYFE AI can review how your organisation has configured Microsoft 365, Copilot, sensitivity labels, and DLP policies, then highlight gaps where AI could still over‑expose confidential emails or documents. They can also design a remediation roadmap covering technical changes, staff training, and ongoing monitoring so you can keep using AI while maintaining regulatory and customer trust.